Unleashing capitalism to ignite innovation

- Sep 1, 2025

- 8 min read

‘Unleashing capitalism to ignite innovation’ goes to the heart of the current economic debate. In the space of five words it confronts a key challenge facing the UK economy, as well as focusing attention on a major opportunity.

The opportunity is that innovation is necessary for economic growth and to address the green agenda, delivering stronger, sustainable growth. The challenge is to unleash capitalism at a time when intervention and the intrusive role of the state is increasing.

In the face of intense global competition the UK needs to be more competitive, with innovation and offering services and products that are better value for money. Instead of rewarding hard work, encouraging investment, and fostering innovation, the current policy environment stifles risk–taking, overburdens businesses with excessive regulation and taxation, and fails to empower the private sector.

The UK has become a low growth, low productivity and low wage economy. That is despite having world class firms and sectors such as the arts, business, and financial services, and top universities, among others. It has also become an economy with high debt and an upward trend to public spending and taxes. This, and the direction of travel, is leading to a wealth drain, as people leave the country.

There is a necessity to turn this around and raise the economy’s trend rate of growth. The immediate omens are not good.

The trend rate of economic growth has collapsed since the 2008 global financial crisis. In the two decades before that crisis, the UK grew by 2.75 percent per annum, doubling the economy’s size every 26 years. Since then, despite cheap money and rising debt, growth has weakened. The Office for Budget Responsibility now estimates trend growth around 1.67 percent, meaning the economy doubles every 43 years. It may, however, be closer to 1.25 percent, a doubling every 58 years. To add to this slowdown, the surge in the size of the population has dampened the growth in income per capita.

We have to contend with a changing geopolitical landscape, as globalisation is replaced by fragmentation, free trade by protectionism, and national security is balanced alongside economic prosperity in decision making. Remaining outside the EU’s single market gives the UK regulatory autonomy in growth areas such as artificial intelligence and being outside the customs union allows trade deals with fast growth economies, such as India.

The UK needs a supply–side agenda that boosts the economy’s growth potential, supported by a credible macro–economic policy framework to reduce debt and keep inflation under control. This needs to focus on investment, innovation and the right incentives for businesses to grow. Against the backdrop of a high debt level, supply–side measures to boost potential growth are as important as addressing the UK’s fiscal problem.

If growth continues to disappoint, it is hard to imagine this Government stepping back and doing less. Instead there will be more intervention, with higher spending and taxes, and more regulations. This intervention is already apparent in terms of the UK’s approach to the green agenda.

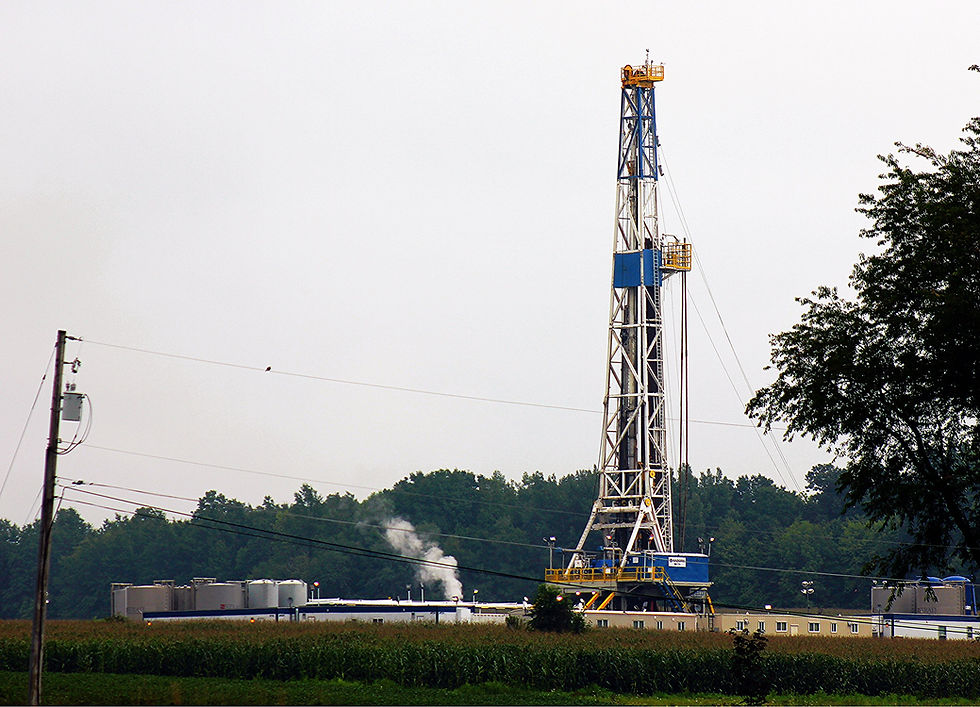

On the positive side the UK leads in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, but the flip side has been intense regulation and some of the highest energy costs in the world. The latter is taking its toll on growth, including the UK’s attractiveness for AI and tech investment, which are heavily energy dependent. So how then can the UK continue to address the green challenge, given the scale of global warming, while keeping energy costs down, to ensure competitiveness and growth? Green and growth need to be compatible, with a pro– business approach.

In particular, ‘unleash’ reflects that regulation, tax and attitudes may be holding back the economy and need addressing. Businesses, and especially smaller ones, complain about the myriad and level of taxes. Small firms also draw attention to the difficulty of raising finance to scale up and invest.

Simplifying the tax system is long overdue even before one starts to address the level of taxation. Recent policies towards non–doms and uncertainty about future tax policy have exacerbated the problem and could dampen the UK’s attraction for entrepreneurs, the aspirational and to inward investors.

For business it’s a similar story with corporation tax now high and the regulatory burden is high and complex.

The net zero timetable is too inflexible and has contributed to current high energy prices. Gradualism is needed as we must have energy prices, at the least, equivalent to European peers. The focus should be on energy addition, not energy substitution, like many other countries who are also moving to renewables.

The economics are that renewables are added to the current mix. Then, as their cost falls, and technology advances, including storage, this allows their reliability to improve, then renewables will displace fossil fuels, eventually substituting for them. In contrast, the UK is moving towards substitution now, when the base load of renewables is low and at the expense of high energy costs. There is a strong case for renewables but the energy mix needs to be diversified and that includes adding to our supply with nuclear.

An energy addition not substitution approach is more gradual than our current policy. It would allow renewables to grow in use. It would allow the domestic supply chains to adjust and that may create more business opportunities to build the green infrastructure such as turbines in the UK, as opposed to imports. The UK sees its energy costs determined by marginal cost pricing determined by global gas prices. Zonal pricing in the UK market has been suggested to avoid nationwide high energy prices, but that can only be temporary and would likely see higher prices in the South East.

Attitudes matter. A mindset change is needed, away from an interventionist approach. Even the International Monetary Fund has been critical of the global shift to industrial policies, which can be expensive and unsuccessful.

Part of a necessary shift is to alter our terms of reference for the performance of the economy, comparing ourselves more with the fast–growing economies across the Indo Pacific, and not just with economies in Western Europe, the world’s slow growth region.

‘Capitalism’ goes right to the core of the present debate, for it is a word that even its supporters seem afraid to use and there is a need to address why that is the case and to put the record straight. Adam Smith, in the Wealth of Nations, talked of the ‘invisible hand’ and the power of the market to deliver. Incentives matter. Smith, also, in the Theory of Moral Sentiments, stressed the ‘visible hand’, namely the importance of moral and ethical behaviour. It is important for the environmental agenda to recognise that the market is efficient, as opposed to a complex regulatory state, and helps minimise inputs in order to maximise outputs.

The importance of the private sector and of the market mechanism in driving future growth and improving living standards should be the focus. It means getting the balance right between the public and private sector.

In the 1980s, public spending fell from 40 percent to 35 percent of GDP. Today, it is over 45 percent and rising as the state intrudes more. After the war, we had a successful mixed economy: a capable state focused on public goods like education and defence and a private sector driving growth.

The state consumes resources, it does not create them. It must rely on a productive private sector to fund it. When the state grows too large, taxes and regulation rise and the private sector is undermined.

Importantly, this is not to deny the role of government. A healthy, educated population is essential, public R&D can crowd in private investment and fiscal policy can stabilise an economy, but the size of the state needs to be kept in check, to allow the private sector to grow. A one–third, two–thirds mix in GDP may be best, but it is hard to be precise.

This leads, naturally, into the priority ahead, ‘to ignite innovation’. We know the criteria that need to be in place for investment, such as more finance and lending for firms, sound macro–economic policies, a skilled workforce, a lack of bureaucracy, the level, predictability and simplicity of tax, future expected demand, plus functioning and supportive infrastructure. These same factors are critical for innovation, too. UK business research and development (R&D) investment has stagnated, lagging behind global competitors.

The City of London has a vital role to play. First, and foremost, it must take a more dynamic role in financing innovation, providing funding to small and medium–sized enterprises, and helping scale up UK businesses. To address UK short–termism, the City needs to close the patient capital gap.

The City has a great opportunity, too, to become the global centre for green finance, particularly when the US appetite for this may wane during President Trump’s second term. There is a large pool of funds looking to invest in green assets, at a time when there is a shortage of these.

Deep liquid markets are needed. London can play a global role too, in the environmental space, being the place to raise funds and to direct money from. For many emerging economies addressing environmental challenges is tough, because of the high cost of capital.

The stakeholders in the City are aligned, in terms of the government, regulators, banks and financial institutions and clients. There is transparency, in terms of the metrics relating to the green agenda and it now fits into risk management, strategy and governance.

Too often innovation is talked about solely in terms of STEM areas and manufacturing, and, while they are important, innovation is an economy–wide issue, not sector specific. The UK, after all, has one of the most powerful service sector economies.

It used to be said that governments didn’t pick winners, the losers picked the government as loss–making firms sought support and intervention. Thankfully we have moved on, but there is no reason to expect the Government’s policy approach will address Britain’s low growth, low productivity problem. As the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) outlined in a timely recent analysis of industrial strategies, the eight sectors chosen are the most productive ones anyway, although interestingly it noted their investment is low. We must avoid a move towards micro–management as an alternative to the supply–side agenda which is needed.

Regulatory burdens also weigh heavily on SMEs, with compliance costs disproportionately impacting them. Tax complexity, employment law and business rates present ongoing obstacles, while the administrative burden of meeting these requirements diverts time and resources away from growth and profitability. Like larger firms, too, SMEs would benefit from policy predictability.

Without bold reform, the UK will continue to underperform. We must avoid being dragged too much in the wrong direction by state micromanagement. Instead there is the necessity to create an environment where businesses drive innovation, entrepreneurship is encouraged and the City provides the capital needed.

The green agenda allows us to see the role of the private sector at work. The government needs to move towards energy addition, and allow energy prices to subside. In turn the private sector can lead the green transition, powered by innovation, investment, and a City well placed to mobilise capital at scale. Opportunities abound from clean energy and smart infrastructure, to low–carbon transport and circular supply chains. It is profit, not subsidy, that will align incentives, unlock enterprise, and drive the innovation needed to deliver a green agenda alongside growth.

Views expressed in this chapter are those of the author, not necessarily those of the Conservative Environment Network.

Comments